Where carbon fails to settle

MIT study demonstrates patchy meadows of seagrass can have limited carbon storage

Seagrasses and other aquatic plants are recognized as “ecosystem engineers” for their ability to physically modify the environment. A meadow of seagrass acts like a natural barrier in the water. It slows down the flow of water and reduces the strength of waves by creating resistance, much like how trees slow down wind in a forest. This creates calm areas where many different species can live, helps clean the water, and encourages carbon to settle into the soil beneath the seagrass, where it gets buried

Furthermore, seagrass meadows help fight climate change by storing carbon in their soil over the long term, which keeps carbon dioxide from escaping into the air. Restoring and planting these meadows could be a useful way to reduce climate change impacts. However, the amount of carbon stored can vary a lot between different meadows and even within one meadow. This makes it tricky to measure how much carbon they can capture.

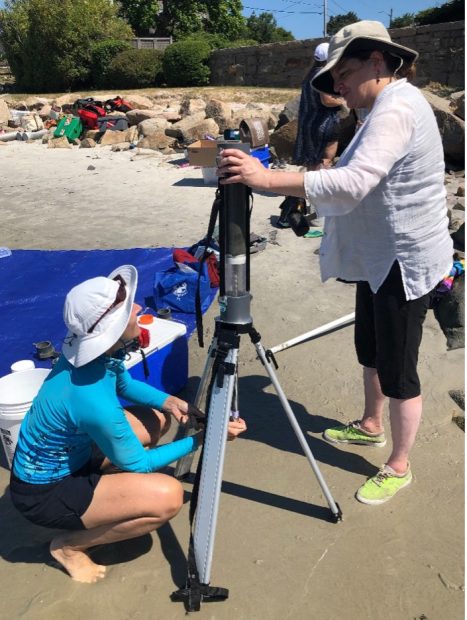

To provide more insight into the carbon storage capacity of seagrass meadows, a group of researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, MIT Sea Grant Program, Boston University, and the US Environmental Protection Agency conducted a study published in Nature Communications – Earth and Environment that examines the spatial variation in carbon across a patchy meadow in Gloucester, Massachusetts.

The study found that water flow slowed within seagrass patches and sped up in the bare areas around them, which should have helped carbon build up in the patches. But when researchers checked the soil, they found no link between where seagrass grows now, how water flows and how much carbon was stored.

“It was surprising that the ephemeral nature of the individual seagrass patches within the meadow could result in little effective build-up in sediment carbon beneath the overall meadow,” says Rachel Schaefer, PhD 24’ and lead author of the study. “This highlights that not all seagrass meadows are good carbon sinks.”

By using remote sensing images to track changes in the seagrass meadow they discovered that the seagrass patches constantly shift, with no area staying covered for more than a decade. The most carbon was found in areas where seagrass had recently stayed for a longer time.

However, the overall long-term carbon storage was zero, likely because erosion removed sediment.

The study found that differences in water flow across a patchy seagrass meadow affected how much sediment was stirred up but did not influence how much carbon was stored in the sediment. The researchers expected vegetated patches to store more carbon than bare areas, but this assumption was based on the idea that the meadow’s layout stayed the same over time.

However, historical images showed that the seagrass patches constantly shifted positions, even though the overall meadow coverage stayed stable. This movement prevented carbon from building up and kept carbon levels similar to bare areas nearby.

The study suggests that understanding a meadow’s history can help determine its potential for carbon storage. If the patches in a meadow stay in the same place over time, they are more likely to store and retain carbon in the long term.

Based on the study results, Schaefer recommends that when restoration managers are selecting locations to restore seagrass, they should use historical aerial imagery to assess the historical persistence and patch dynamics of seagrass in those areas.

“If carbon credits are a key motivation for a restoration effort, managers should aim for the restored meadow to be continuous (near 100% area coverage), as continuous meadows can not only enhance carbon sequestration but also can sustain this enhancement over long periods of time,” says Schaefer. She also notes, “establishing entirely new meadows could be more expensive and riskier than restoring degraded, patchy existing meadows. Restoration could help the fragmented patches within a meadow coalesce into a stable continuous meadow and likely enhance carbon sequestration and other ecosystem services.”

Other authors of the paper include Phil Colarusso, marine biologist at the U.S Environmental Protection Agency, Juliet Simpson, coastal aquatic ecologist at MIT Sea Grant, Alyssa Novak, Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Earth and Environment at Boston University, and Heidi Nepf, Donald and Martha Harleman Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at MIT. The research was funded by the MIT Energy Initiative.