CEE leads environmental hands-on demonstrations at the Cambridge Science Festival

Two CEE labs showcase how nature and natural materials can improve and sustain our planet

Students and postdocs in the MIT Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering led hands-on demonstrations for the Climate Day events on October 6 at the 2022 Cambridge Science Festival. The demonstrations were held at the new expanded MIT Museum.

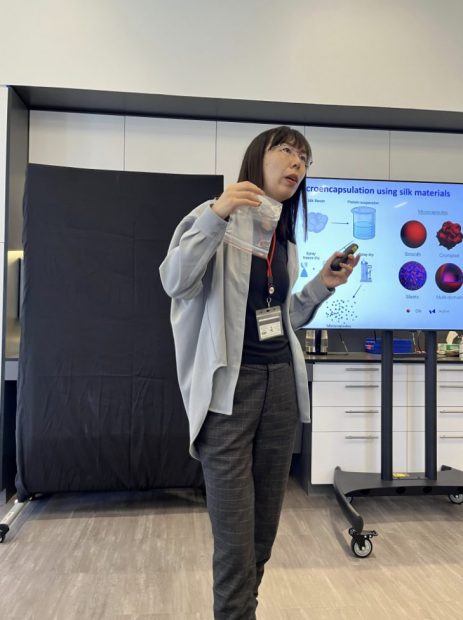

Associate Professor Benedetto Marelli and postdocs, Muchun Liu and Yunteng Cao gave an afternoon talk and demonstration on “Silk Offers an Alternative to Microplastics” to showcase the latest research out of the Marelli lab.

Microplastics are tiny particles of plastic that are found worldwide in our water, air, and soil. Despite being a harmful pollutant, they are often intentionally added to everyday items such as paints, cosmetics, and agricultural products.

Postdoctoral Associates Muchun Liu and Yunteng Cao have worked with Professor Marelli to develop a biodegradable alternative to these microplastics based on silk.

Cao begins the demonstration by cutting a silk cocoon into several pieces and processing it in a boiling water solution. Overtime, the glue protein that keeps the fiber together dissolves. The silk fibroin then can be reengineered into different forms, including film, micro-particles, micro-needles and so on.

Concern over microplastics and their effects on the environment and our bodies has been increasing. “Microplastics do not degrade, they persist much longer than our human life,” Liu says. “Right now, we don’t know the health implications, so it can be a risk.” The EU has already proposed that added microplastics must be eliminated by 2025, and more regulations are on the way.

After the silk is prepared in a water-soluble suspension, a spray drying method is used to prepare the capsules. The spray drying method works similarly to a hair dryer, Liu explains, using hot and rapid air to dry the water contained micro-droplets quickly.

From this process, a silk encapsulation can be developed, offering a replacement to the microplastic based encapsulations that have traditionally been used to contain herbicides used on crops. The silk encapsulation allows for a slow release of the herbicide, protecting both the farmers and the crops.

The question of cost and sustainability was raised by one event attendee. Marelli explained that silk is relatively inexpensive, and they can even make use of the wasted silk fibers that couldn’t be used for textiles. As for sustainability, Marelli notes that an application specific life cycle analysis must be performed. Since 90 percent of silk production occurs in China, shipment of silk could have an impact on the carbon footprint of the supply chain, but new sources to be developed. “While microplastics can take hundreds or even thousands of years to decompose, silk is a biodegradable material,” says Marelli.

Building with Nature

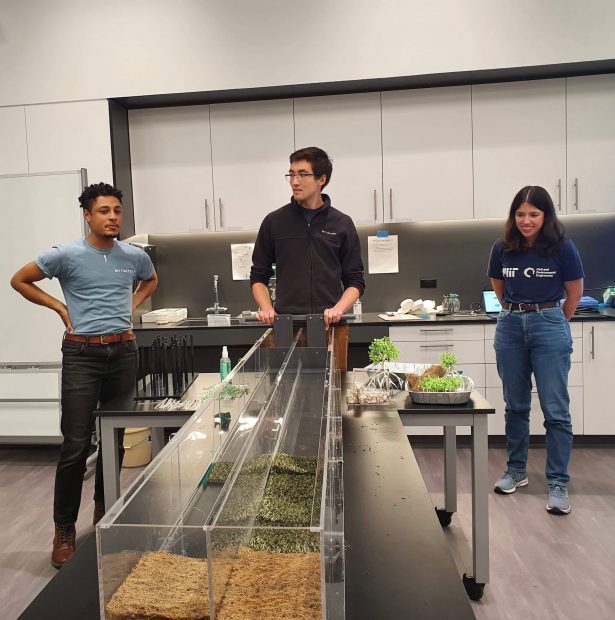

Graduate students in the Nepf Lab, Autumn Deitrick and James Brice gave an evening talk and hands-on flume demonstration on “Building with Nature: Resilient Coastlines for our Cities and Ecosystems” to show how ocean waves interact with natural and man-made materials on our coastlines.

Coastal areas are vulnerable to climate change as sea levels continue to rise and storm surges destruct and flood these areas. Introducing green infrastructure such as seagrass, salt marshes and mangroves provide environmental, social, and economic benefits for coastal resiliency.

“For example, mangroves dissipate energy from the waves to slow down the surge of water,” says Deitrick, PhD student in the MIT-WHOI program in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. Pointing to a small replica, Deitrick shows attendees the complex root structure of the plant. “Water twists and turns through the roots, stripping away the energy from the ocean waves, preventing coastal erosion.”

“Seagrass also plays an important part in holding down wave energy by stabilizing sediments on the seafloor, preventing a seascape of shifting sand and mud,” adds Brice, graduate student in the Departments of Architecture and Civil and Environmental Engineering. “Both mangroves and seagrass also absorb nutrients, and trap sediments, helping to improve water quality.”

Besides coastal protection, Deitrick notes the added benefits of green infrastructure also include more fisheries, habitats for aquatic life, and diverse ecosystems like oyster and coral reefs that attract tourists and improve community life and property value.

Attendees had a chance to experience for themselves how waves interact with vegetation by making waves in the demonstration flume. By comparing the different vegetation in the flume, participants could see how the geometry of the vegetation impacts the wave energy.

Some of the questions raised from event attendees included restoration and conservation efforts for seagrass, mangroves, and salt marshes.

“If you have an area to restore, it’s important to establish the hydrology first so the system is set up to thrive,” says Deitrick. “If you establish the conditions where mangroves are nearby, the mangroves will colonize the area and begin to grow.”

Professor Heidi Nepf adds that restoration of seagrass takes a lot more effort because of its delicate root structure and needs assisted migration in colder coastal areas. “While restoration efforts for salt marshes will often set up oyster reefs in front of the marsh to break up the wave energy to prevent erosion,” says Brice.

Seagrass and mangroves also help with climate change mitigation by trapping carbon-rich sediment underground, not allowing it to re-enter the carbon cycle.

“Plants are the real magic when it comes to climate change mitigation, and we as researchers are just trying to understand them,” adds Deitrick.

The two workshops were funded by the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering to engage the local community with an educational overview of the research from the Nepf and Marelli labs that use nature as a tool to build a more sustainable planet.