Egypt could face extreme water scarcity within the decade due to population and economic growth

New study shows Egypt will import more water than water supplied by the Nile if changes are not made

Egypt will import more water (virtual water) than the water supplied by the Nile, if the population and the economy continue to grow as projected – according to a new study from the MIT Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

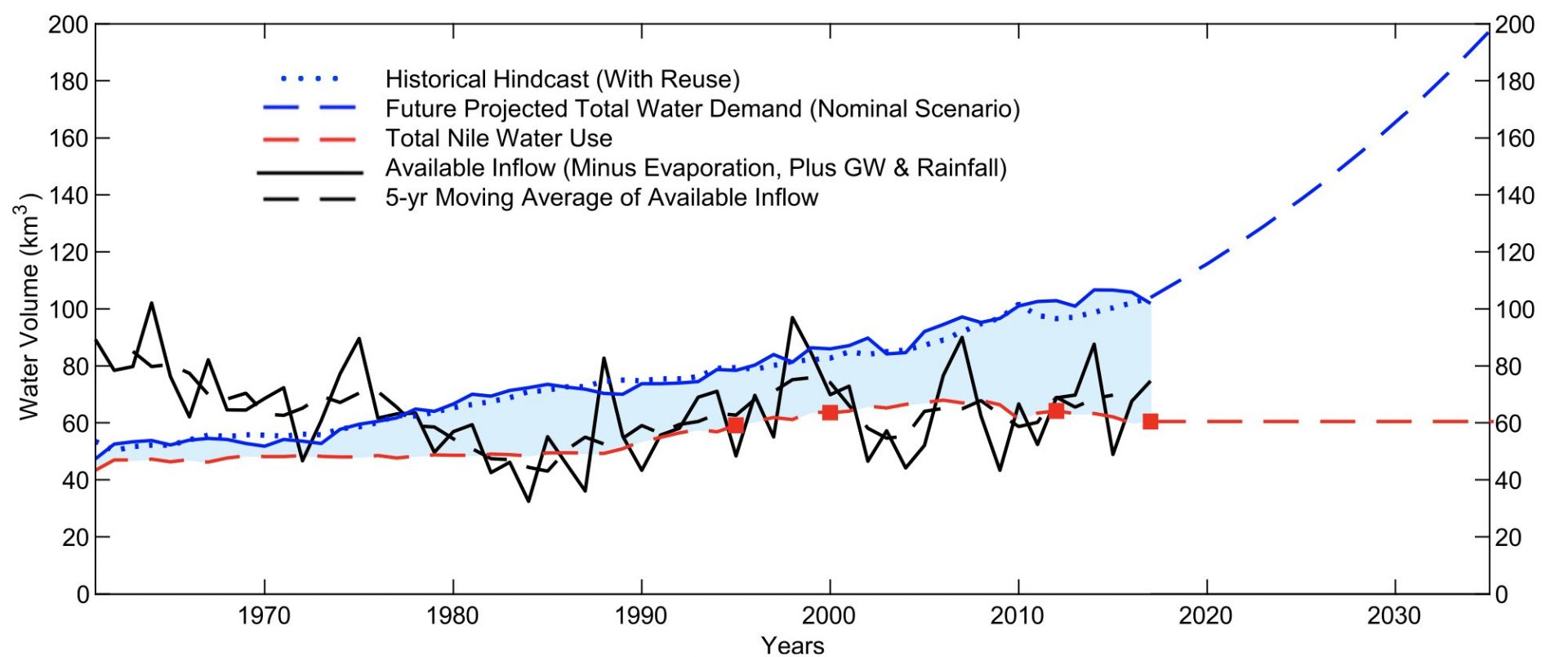

The study published in Nature Communications shows a historical reconstruction of where the water supply in Egypt is going under conditions of population growth and a developing economy.

The research also provides recommendations of ways Egypt can sustain and leverage water supply for a more sustainable future.

Agriculture is an important sector of the Egyptian economy and for millennia the Nile supplied Egypt with more water than needed. Approximately 90% of the water from the Nile goes towards Egypt’s agricultural production, but as the population grew and the economy expanded, demand on water also increased.

“When you have more people, you need more food, but also as the economy gets better and trade connections improve, the nature of people’s diets also changes”, says Catherine Nikiel, PhD student in Civil and Environmental Engineering and lead author in the study. “You have people who might start consuming more meat and consuming just different things than they did in the past, which impacts their agriculture.”

The historical reconstruction allowed the researchers to take a granular view into the past and future trends of consumption to see where the water demand is increasing.

Starting in the 1970s, once Egypt started using all the water the Nile could provide them, they started importing more food. A large proportion of their crops of wheat and maize are really water intensive to grow, need a lot of area, and can’t support efficient irrigation methods. Egypt eventually started importing as much corn and wheat as they grew. The researchers then began to see how much Egypt is importing versus how much they are using to project that within the decade, they will be importing as much virtual water as they’re pulling in from the Nile.

“We know that their imports are rapidly increasing so at what point does that balance shift, where they’re actually more dependent on external water than on internal water,” says Nikiel.

The researchers also present recommendations on how Egypt can leverage water resources.

“By shifting production from high water use low-cost crops such as corn, maize, and wheat to higher value lower water requirement crops like fruits and vegetables, which are very profitable on the market, and better suited to really high efficiency irrigation methods and selling those for profits to import maize and wheat, they can potentially shift that balance even further,” adds Nikiel.

The researchers illustrate that the future of water in Egypt is reliant on external cooperation with its neighbors and its own ability to optimally manage internal demand and use of water. The study claims, “Adaptations are ultimately in Egypt’s best interest, as they allow for continued growth and prosperity with more careful management of resources. Egypt has the chance to be an example for other developing water scarce nations, and a leader in the Nile Basin. If changes are not made it will soon serve as an ecological cautionary tale with implications for the entire region.”

“Past and future trends of Egypt’s water consumption and its sources” is published in Nature Communication and may be read online. Co-author of the study includes Elfatih A. B. Eltahir, H. M. King Bhumibol Professor of Hydrology and Climate, and Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

For more information and research regarding water and climate in the Nile River Basin, readers are encouraged to explore the publication “A Path Forward for Sharing the Nile Water: Sustainable, Smart, Equitable, Incremental” by Elfatih A. B. Eltahir, with contributions from Catherine Nikiel and others.