A Discussion Over the Ethics of Mummified Hands

By Sophia Mittman ’22

While I’m here in Italy, I have been completing most of my research at the Museo Egizio of Turin, which is home to the second largest collection of Egyptian artifacts in the world, second only to that held in Cairo, Egypt. Each morning when I enter the museum, I walk past the Gallery of Kings, where a dark room with epic lighting displays large stone Egyptian statues of pharaohs, gods, and sphinxes, like those you would imagine you would see in the movie, “Night at the Museum.” After weaving through display cases filled with old parchment scrolls, stone slabs covered with countless figures of hieroglyphics, and well-preserved pottery, I enter into my main workspace in the registrar’s office. Some days I am the only one working at my desk, while other days visiting professors from universities like UCLA are sitting on the other side of the table analyzing ancient Egyptian sandals or are taking samples from woven bowls of thousand-year-old dried—and practically mummified—fruit.

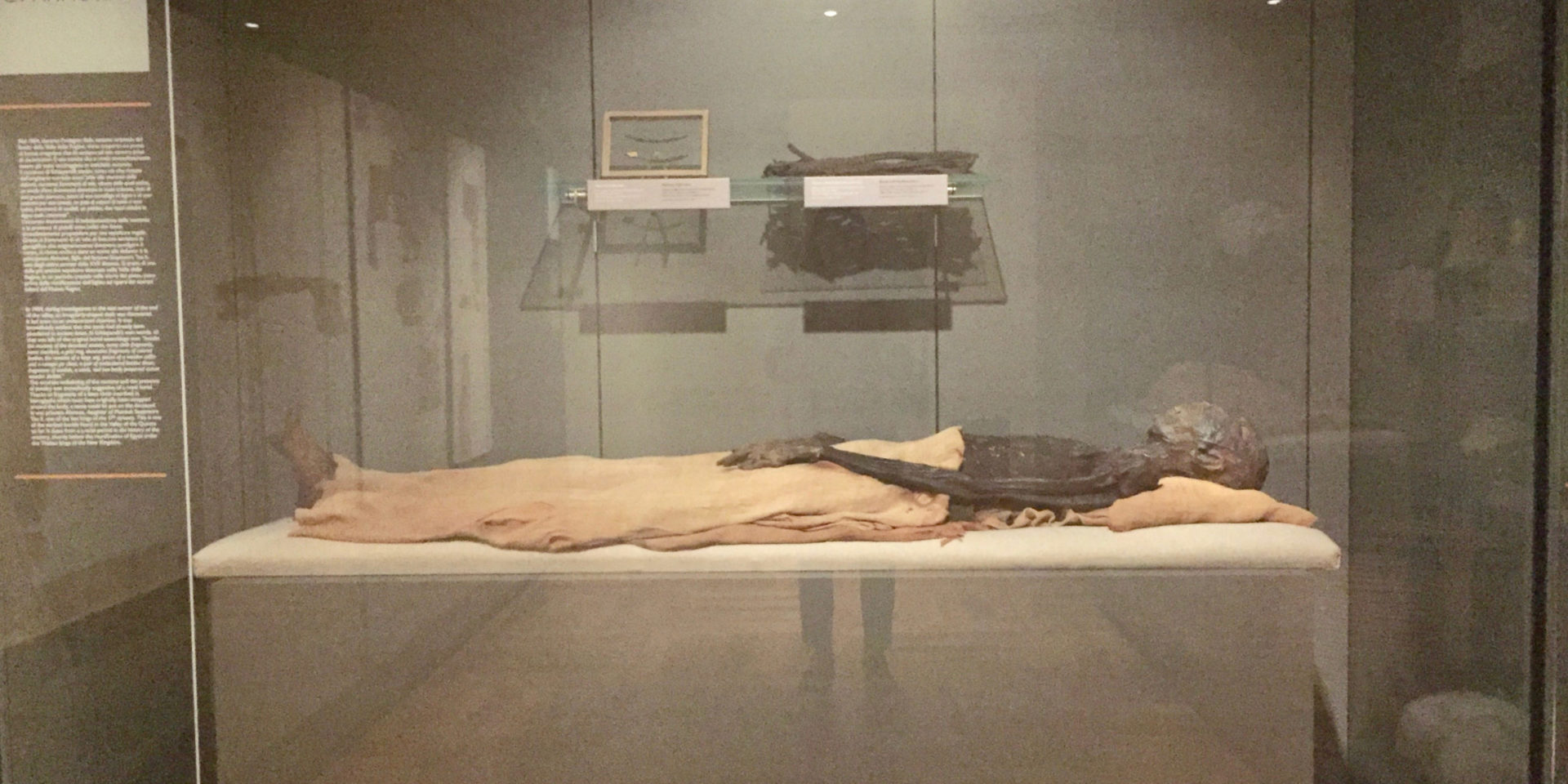

Intact mummy of Amhose

On one particular day, I met a graduate art conservation student who works in the restoration lab in the registrar’s office. He could tell that I was a curious student, so he gave me a mini-tour of the project that he had been working on. I walked into his lab and saw two mummified hands on the table, swaddled carefully on top of pieces of Styrofoam, one facing palm-up with its cloth wrappings still intact and a golden ring peeping out of the strips, and the other resting palm-down without any of its wrappings covering the dried skin, long past turning a dark wooden-like color. I must say, it was certainly strange yet still fascinating to examine the two hands from less than a foot away without glass to separate them from me as ancient pieces of cultural heritage are normally in a museum. I was surprised to find that the student had done similar analysis processes on the hands as we had done during ONE-MA^3 on other artifacts. He had modeled the hands on his computer and had mapped different areas of the hand, each section corresponding to different sections that needed repairing and the parts he had already restored. When it comes to restoring the fragile hands, it is forbidden to change or alter the original form of the cultural heritage, for example, by removing any piece of the wrappings or by cleaning any more than the outermost layer of dust that has accumulated on the surface. We were taught similar rules about art conservation in ONE-MA^3 when we had visited the art restoration labs of the Vatican Museums. When restoring artifacts like these hands, portions must only be restored so that those pieces cannot be damaged further or lost (he accomplished this by patching loose pieces of the mummified hand with small, nearly-invisible pieces of special Japanese paper).

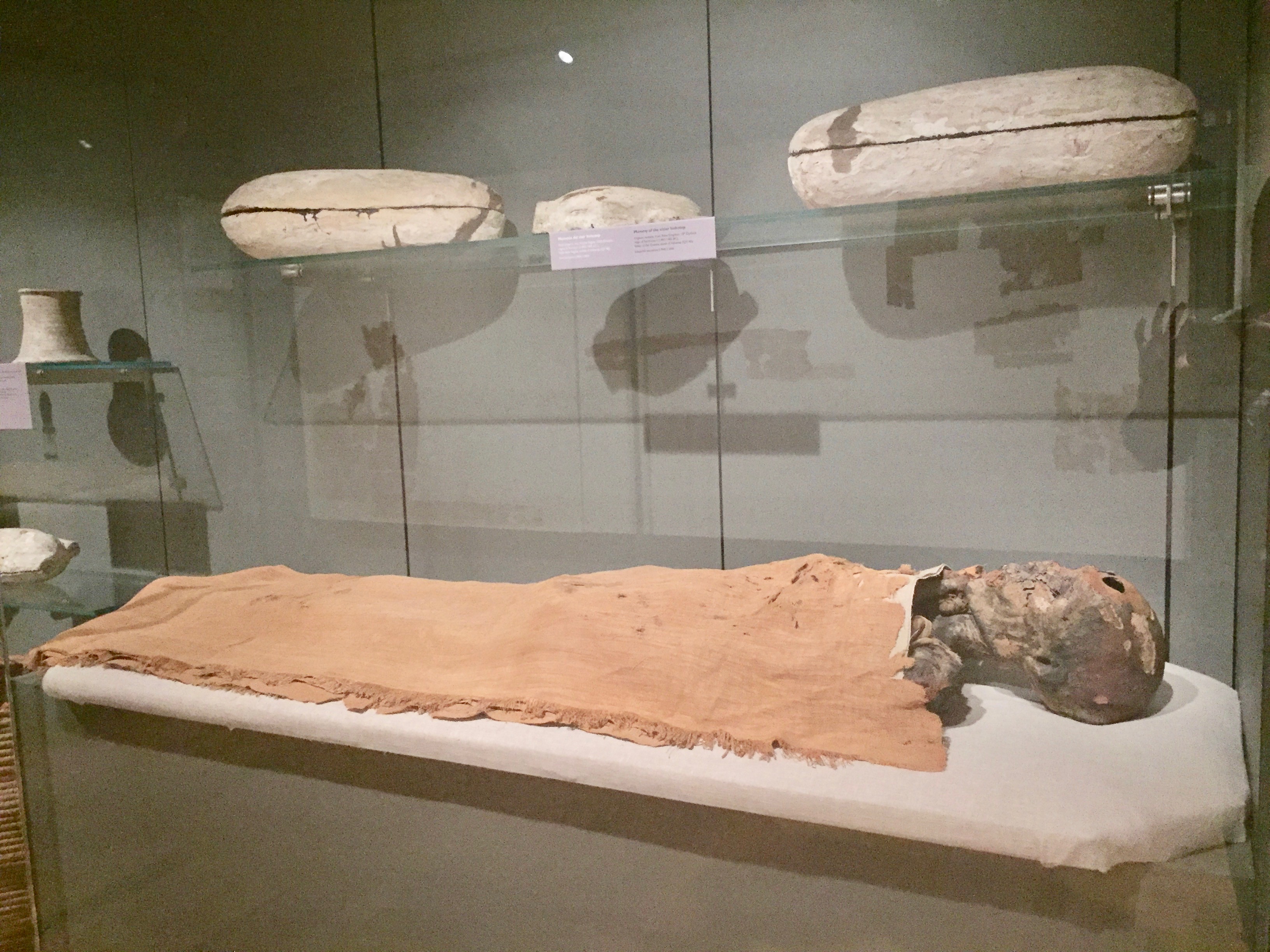

Entire mummy of Imhotep

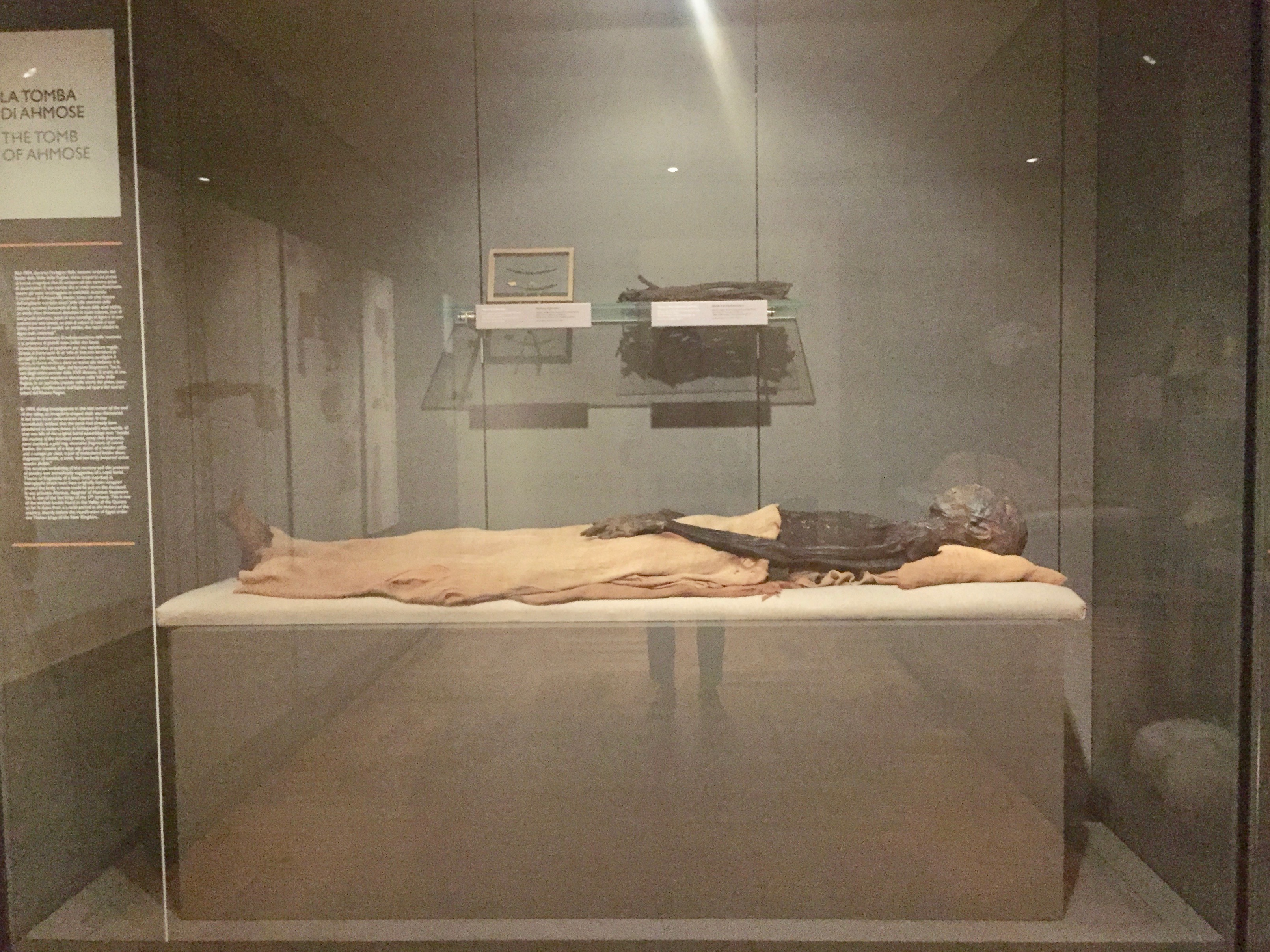

I inquired if the hands would then go on display in the museum once he had finished restoring them. I quickly learned that the short answer is: absolutely not! These mummified hands are indeed pieces of priceless cultural heritage, but different museums have different approaches to dealing with ethical questions when it comes to displaying that cultural heritage, especially when human remains are in the conversation. In short, I learned that the Museo Egizio, as an archeological museum, does not look to display single mummified extremities that are separated from a body simply for public entertainment. If they are to display mummified human remains, they usually will only do so if they have the entire body intact, and more importantly, if they know certain pieces of information about the person who lived thousands of years ago. For instance, there is a room in the Museo Egizio that displays two complete mummies without their wrappings. On the display cases is the entire story of the two mummies, Ahmose and Imhotep. There is another complete mummy on display, curled up into a fetal position. Archeologists were not able to identify who exactly this man was, but along with the display case, they included an explanation that described as much information about this person as possible. In this way, the museum is able to display cultural heritage in a manner that is ethical, considerate, and respectful toward the humans who walked on Earth long before we ever did, and I believe that this same consideration of ethics is essential when it comes to displaying most other forms of cultural heritage, too.

Mummy of a 40-year-old man from the Predynastic period

Share on Bluesky