Guest speakers and panelists inaugurate new MIT climate major at half-day symposium

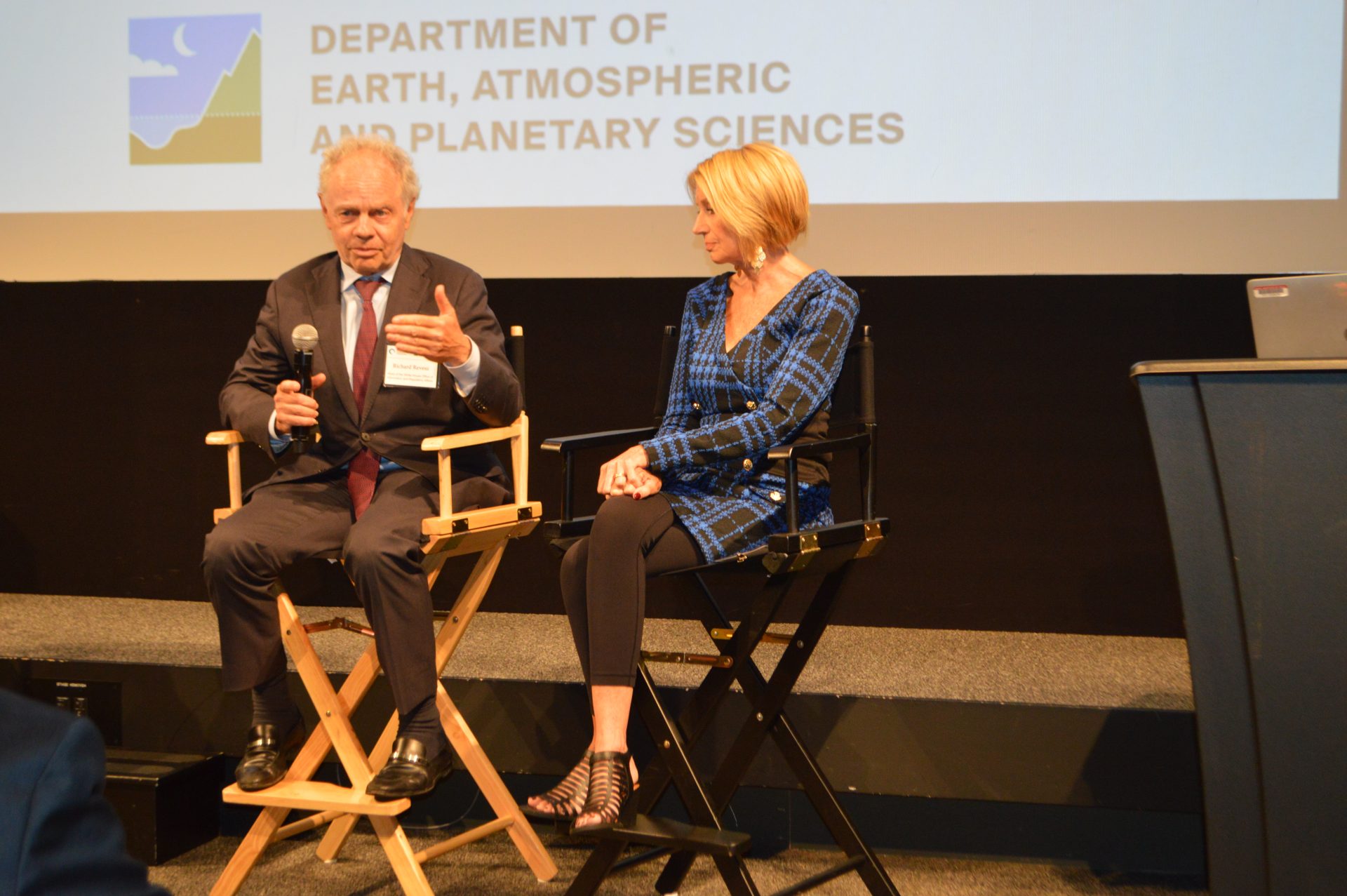

On a rainy September day, accented by more extreme weather-related news of the catastrophic flooding in Libya, students, postdocs, and faculty gathered for the 1-12 Climate System Science and Engineering degree half-day symposium hosted by the Departments of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE) and Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS). The symposium served as a way to introduce the significance of the new climate major to the MIT community. Guest speakers, Administrator Richard Revesz, who leads the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs at The White House Office of Management and Budget, opened the event alongside Marcia McNutt, president of the National Academy of Sciences. Both speakers shared their enthusiasm for the new bachelor’s degree and its relevance to leading the charge on climate.

In Revesz’s address, he talked about his own academic and career journey from his time at MIT as a master’s degree student in civil and environmental engineering and discovery of his interest in the public policy side of science and technology problems, to his law profession and current role working for President Biden.

“I wanted to pursue a joint major in civil engineering and public policy. Combined majors of this sort are fairly common now, but that wasn’t the case then,” said Revesz. Even when others on his path suggested he abandon his plans for law school to pursue a PhD, he stuck to his original plan.

He describes a serendipitous moment at MIT, when his advisor suggested he take a graduate microeconomics sequence that is required for PhD students in economics.Knowing less economics but more mathematics than other students in the course, he discovered it was a worthwhile trade-off. The course greatly enriched Revesz’s intellectual journey in law school, his work as a legal academic over the last 40 years, and his current work as a public official.

“Because of my own experience, I’m thrilled that the Climate System Science and Engineering major requires students to work with their advisor to choose elective subjects in a broad range of social science disciplines. While STEM subjects provide a foundation for understanding the natural world, social science electives will teach our future leaders how to make use of their scientific understanding when making public policy,” said Revesz.

Revesz also illustrated five public work examples his office is charged with from President Biden’s directive that parallels with the learnings of the new degree. One of those is quantifying and monetizing the social cost of greenhouse gases.

“In connection with your studies, some of the most important effects of greenhouse gas emissions on climate are currently uncaptured in estimates of the social cost of greenhouse gasses. For example, current models of climate change damages include the effects of average temperature changes, but do not include the effects of extreme temperature events or the effects of increased temperature variability,” said Revesz.

Similarly, Revesz explained that current models capture certain effects of sea level rise but do not capture effects from changing precipitation patterns, the intensity or frequency of extreme weather events, or oceanic acidification. “Progress and accounting for these effects will require new theoretical and empirical research,” he said.

Guest speaker, Marcia McNutt followed Revesz’s remarks with her talk about Convergence for Climate Change Innovation.

“There are at least two things that MIT is world-class in. One is innovation, and the other is in convergence science. And convergence science is exactly what we need now for climate change,” said McNutt.

Convergence, a concept that originated at MIT from Nobel Laureate, Phillip Sharp, refers to the integration of the sciences with engineering and information technology to solve human health challenges. McNutt described why we need convergence for climate change and how the partnership between EAPs and CEE brings this concept to the forefront.

“We need the geoscience just to understand what will happen. If we don’t understand our climate future, we don’t understand what problems we need to address and what unintended consequences we need to avoid. Engineering can tell us what we can do about what’s going to happen to come up with new solutions,” she stated.

She describes the areas for where innovation and engineering are needed for a zero-carbon future, such as the ability to store six terawatt hours of energy.She also talked about the climate crisis effects on health and equity.

In response to a question about whether or not researchers should study geoengineering, in particular albedo modification, she responded,“We have to figure this out before we’ve got our back against the wall,” she said. “Imagine a future when we’re in crisis, and we don’t know if the cure is better than the disease, so there are studies that absolutely need to be done.”

She concluded to the audience of MIT community members, “What’s essential to climate change is innovation and science education, and that’s exactly what you’re doing today.”

Following guest speakers Revesz and McNutt were three faculty panelists, Kerry Emanuel, Desirée Plata, and Dara Entekhabi, in addition to MIT senior Anushee Chaudhuri, Solomon Assefa, vice president for climate and impact science at IBM, and Sabrina Shankman, climate reporter for the Boston Globe. They all shared their personal experience that connects the relevance of the new climate major and emphasized the importance of the joint effort between engineering and science.

Kerry Emanuel, MIT Professor Emeritus of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences talked about the concept of risk and its role in bridging climate science and policy. Emanuel pointed out that the insurance industry has traditionally relied on historical hazard statistics, which has led to artificially low rates in high-risk areas, hindering the public’s understanding of climate risks. Emanuel addressed the need for climate scientists and engineers to work together to quantify and communicate weather hazard risks more effectively, using advanced modeling and AI tools.

Following Emanuel was Desirée Plata, Gilbert W. Winslow Career Development Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, who highlighted the unique perspective and potential of MIT students who come to the Institute with a desire to learn fundamental science and drive towards impactful solutions. But are often challenged from the disciplinary silos that have constrained what students are able to do.

“I’m very excited about Course 1-12 because it’s time for us to really start to break that model and empower students with the tools they need to work on the problems they really care about,” said Plata

She also touched on MIT’s role in training future leaders for change and the challenge awaiting MIT students of decoupling economic prosperity from negative impacts on the climate, using nature’s own principles. “Or as someone in CEE might look at the sustainability challenge, as a complex logistic problem.”

“We are fortunate at MIT to be able to leverage the history in logistics and optimization with the understanding of how nature works so that we can start to reimagine our systems for an improved future,” concluded Plata.

Dara Entekhabi, Bacardi and Stockholm Water Foundations Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences discussed MIT’s historical moments of shifts, highlighting how those pivotal moments have shaped the institution’s direction and culture. He emphasized that the new climate major is another such transformative shift. Entekhabi also highlighted, the unique dimensions that climate change adds to engineering design, including lifecycle analysis, considerations of justice and equity, and its effect on human health, providing an opportunity to reinvent engineering in the context of climate challenges.

Speaking over Zoom, Solomon Assefa, vice president at IBM Research and MIT alumnus, leads a global team of scientists and engineers across the world, focused on both the adaption and mitigation side of climate change. He pointed out the ways in which AI is being used to address climate change challenges and analysis and prediction of extreme weather events effects on health-related risks. Assefa emphasized the importance of global collaboration and shared examples of IBM’s work in flood detection, health data analysis, and collaboration with the MIT Climate and Sustainability Consortium. He underscored the significance of integrating technology and research into accessible solutions for climate change.

“Making sure we’re really thinking in a global way in advancing these efforts is what’s going to benefit [IBM} a lot from all the new graduates that will be coming out of this new degree program,” said Assefa.

Sharing the student’s perspective, Anushree Chaudhary, who is President of the MIT Student Sustainability Coalition demonstrated her experience navigating the climate and sustainability space at MIT with a crowded slide of images of all the names and logos of the student groups, departments, labs, and centers working on climate change.

“As a first year coming to MIT and trying to figure out how to navigate this space, it can be quite confusing,” she told the audience. Because of this, the MIT Student Sustainability Coalition formed in the summer of 2020 for the need to centralize and coordinate among these groups.

She explained her own personal climate journey as she started off majoring in materials science and engineering, then switching to civil and environmental engineering before landing in her current major studying urban planning and economics in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning.

“If Course 1-12 were an option in my journey, that would have been calling to me,” said Chaudhary. “I’m really excited to be able to guide first year students with this new major in mind.”

Closing the panel was Boston Globe Climate Reporter, Sabrina Shankman who discussed her work in translating the urgency of climate change, shining the light from an accountability standpoint on where there are barriers to action, and help people understand how climate change is happening in the world around them.

She also expressed how climate change is a story that she can tell quite locally because of how it’s happening, from the 11 inches of rain that fell in Worcester County overnight and the dams that are about to burst, to teachers who were in 90-degree classrooms this summer, or from the deep freeze this past winter that caused heat pumps to stop warming.

“People really want stories about solutions and where they can really ground their understanding of this complex problem and things that they can do,” said Shankman.