MIT Great Barrier Reef Initiative: Cutting Coral Cores

By Zoe Lallas ’20

Working at the Australian Institute for Marine Science (AIMS) the past two months has been full of learning experiences and odd jobs. Each member of the Great Barrier Reef Initiative was able to take on at least one side project during our time here. I was lucky enough to get the opportunity to work with the Coral Core Archives – home to one of the largest collections of mined coral cores in the world.

AIMS serves as a revolving door for visiting scholars and specialists who choose to complete internships, pursue research opportunities required for their degree, or partner with lab spaces in order to obtain access to state of the art facilities in exchange for broadening a web of knowledge. This final category is where I found a PhD student from Boston University. She has spent the last two months at AIMS cutting, preparing, and testing coral samples she has obtained over the past year. Her focus during her undergraduate degree was geology, but in continuing her education, she discovered her interest in climate research specifically.

Coral Samples

It turns out that coral is an incredibly informative record of past climate events. Exposing cut samples to various tests allows us to determine growth rates, bleaching occurrences, water temperature, chemical composition of the resident waters, and many other sets of data. This data is used threefold: to corroborate existing data, and help build a more robust picture of the world at any given point in time, to provide insight on the state of the world from before computer models and other forms of records, and most importantly, to help predict what exactly will occur in the future.

Coral Samples

Originally, Amber and I were lucky enough to receive a tour of the lab within my first week here. Everything the lab supervisor said and explained made me more than eager to spend some time in the lab. More specifically, the types of tests they were running, were all tests I was familiar with: x-raying the corals to see the specific banding and growth, using luminescence to examine sediment deposit rates, and exposing the corals to RAMAN spectroscopy to uncover sediment makeups. The main difference was that I had never seen or used these techniques in the context of annual analysis. I was immediately intrigued by the shear amount of data the lab was able to gather about any given section of ocean or coral over a period of time. The results from testing are so consistent and can really be conducted at any point in a coral’s lifespan because coral doesn’t melt or change with time once it’s dead.

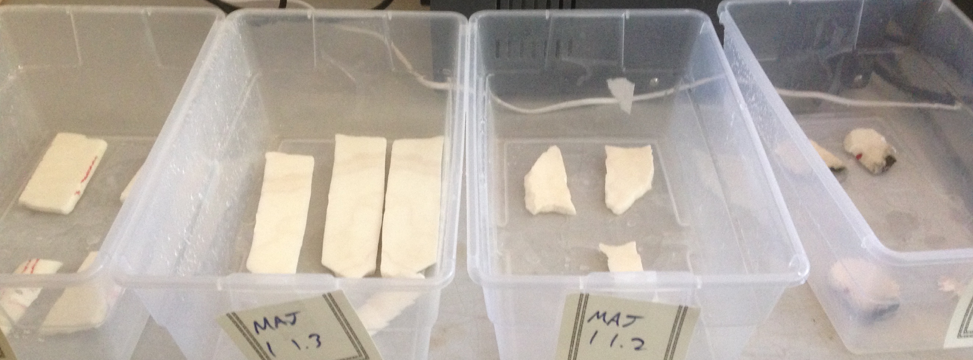

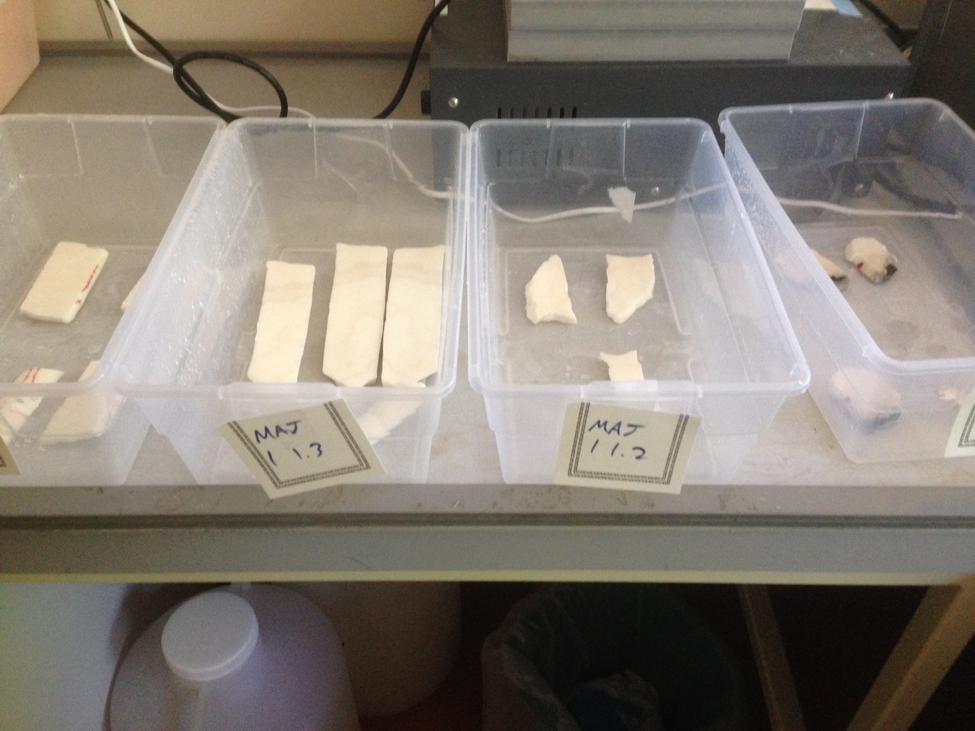

Coral Samples

I was lucky enough to be able to help out with cleaning the PhD student’s samples as they were cut into 5mm thick slabs for sulfur dating back in America. I’m not exactly sure what sulfur dating is explicitly used for, but I know that it allows us to corroborate our knowledge of the world before we have other records. In turn, this allows us to better predict the state of the future. During the student’s time at AIMS, the diamond saw used to cut the coral had been broken and backlogged, grinding her progress to a halt as she had upwards of 60 coral cores that all need to be cut three times to get the proper number of slabs at the right thickness. Cutting coral is not particularly rigorous, just time consuming and repetitive. It requires being near the giant saw, resetting the coral every 5-10 minutes, and letting the incessant buzzing drone in your ears as you attempt to get other work done. There is also the process of corralling and organizing the 5mm samples, and keeping track of which pieces have been cut from which corals. Add this to a very in-depth cleaning process to guarantee the surface of each coral is pristine for testing, and you can easily be set back.

Saw cutting coral cores into thick 5mm slabs

My job was enticingly sold to me as “boring, menial, and incredibly annoying.” However, I couldn’t wait. Anything to be able to work with the coral core archives was more than enough for me. I was expected to handle the cleaning process of the coral because that’s where the lab needed the most help. As it turns out, cleaning coral, is a lot like cleaning teeth. I literally used a water pick (this is a device used in place of traditional string floss to floss teeth) to get rid of the first layer of sediment from all of the samples. I liked to think of the water pick as coral power washing instead, it was much more exciting that way. After all the samples from any given core were blasted with the water pick (tiny power washer), I would have to put them in a sonicator bath for 10 minutes at a time. A sonicator is a sonic motor submerged in a water bath and atop this sits another water bath. These water baths are filled with SuperQ water, which is hyper deionized and exclusively hydrogen and oxygen. The same water is used with the water pick to fully remove any possible contaminants from the surface of the cored samples. The samples are sonicated at three times, or until no sediment remains after the samples are removed. After this is complete, the samples are laid out to dry before being labeled and bagged for their transport back to America.

More coral cores!

The only drawback about the sonicator, is the noise. It buzzes incessantly like a dentist, drilling a hole in your jaw. You hear it inside your head, and feel it in your teeth. Under normal circumstances, I would’ve absolutely abhorred that as my background noise for 9 hours every day. However, because I was contributing to furthering our understanding of the world and had the opportunity to work with coral cores ranging in age from 20 years to well over 500 years, I couldn’t have been happier.

Zoe Lallas ’20 is spending the summer in Australia and New Zealand and participating in a new research and engineering project in collaboration with the Australian Institute of Marine Science and James Cook University on the Great Barrier Reef. [/fusion_text]